in the thicket: a green revenge

enduring weeds & rain, adaptation of the sinuses

"Me and my freedom fighting flowers frolicked to survive the/ scissoring, up-digging, poisoning/ Warning Signs hovered like low hanging clouds:/ No Blooming Allowed; Blossoms Will be Prosecuted/ These brave plants grew just for me/ Grew in spite of a society that favored a monochromatic landscape" - from Black Dandelion by Semaj Brown

Hello garden creatures, it has been a minute since I last updated this newsletter. Between midterms approaching, freelance assignments and of course, developing climate resilience research projects with my high schoolers, I’ve been spending time gearing up for my book release, including finalizing proofreads, gathering information about readings, and of course, savoring my book cover! She is here and she is green and juicy:

Speaking of things that are green and juicy, an early blooming season is emergent, as an unseasonably warm winter complemented by a rush of rain has left the Bay Area drenched in tenderness and in color. It has also emboldened a healthy population of sinus irritants! Climate change has been linked to a longer allergy season – as someone who never dealt with allergies growing up, watching myself join the many runny noses, itchy eyes and drowsy bodies, has been a lesson in self discovery. In the raspy baritone of the late great Charles Bradley, I’m going through changes!

Healthy wind gusts bring waves of pollen, the shaking vegetation of trees and shrubs and flowers alike dance with desire. In a place like California, so biodiverse in its plant community, all inclusive of native plants, invasives (though that name is fraught with multiple meanings), and crops, a symphony of plant flirtation makes for an explosion of color and daily headaches. It’s hard to accept the impending doom and gloom of the “end of the world” when it is so beautiful and cacophonous!

Pollen from different plants tends to come at different times of the year: in the Bay Area, juniper bushes, cedar and oak trees begin releasing pollen in January, annual grasses tend to explode during April and into June (though the timeline is being pushed up every year as climate change worsens), and we don’t really deal with “weed” pollen until the summer. Thanks in large part to European colonization, the United States copes with a variety of nonnative weeds such as dandelions and English Ivy, but there are some “weeds,” or maybe more accurately, plants that seriously outcompete others and offer little benefit to humans that are native to the US, such as oxalis and giant ragweed.

Last year, I wrote a review of Lives of Weeds: Opportunism, Resistance, Folly and interviewed the author, John Cardina; this book has been floating through my mind since I read it, and has definitely enriched my own writing process, as much of my work deals with socio-ecological encounters. Weeding is a form of containing wildness; but weeds are also plants that are indeed “placeless,” forced out to colonize land elsewhere, oftentimes doing it with incredible verve and resilience. Weeds or, and what makes a plant a “weed” is often socially determined. The concept of a weed, a plant that is a nuisance or pest, has social implications as well.

My grandmother was a ruthless purveyor of her flower garden, seeking out dandelions, plantain weed and purslane with a keen eye and eradicating any signs of their presence. Her tulips were her grandchildren too, and there could be no sneaky squatters disturbing their grounds. Elders in my family used to say I “shot up like a weed,” always a skinny, wiry child, I grew faster than all of my cousins, so awkward in trying to get used to a body that was evolving by the week. My cousins and I used to sneak out into the far corners of the backyard, away from our parents’ watchful eyes, to make wishes on dandelions, marveling at how the air dispersed the delicate seeds. But still we were taught to weed out the bad, cultivate the good. Weeds were an eyesore, a burden, an indicator of social class – we couldn’t be caught with our garden looking too wild. Funny enough, heavy herbicide use tends to lead to the proliferation of these plants elsewhere – we don’t die, we multiply.

I am reminded too of the invocation of the rose that grew from concrete, a popular Tupac Shakur poem that may have originated from Ben E King's 1960 song Spanish Harlem from the line, "it's growing in the street right up through the concrete." We are not the weeds, but the flowers that emerge through harsh conditions. Because a rose is still a rose, and it’s important to see ourselves reflected in that which is beautiful, which is vibrant. I agree.

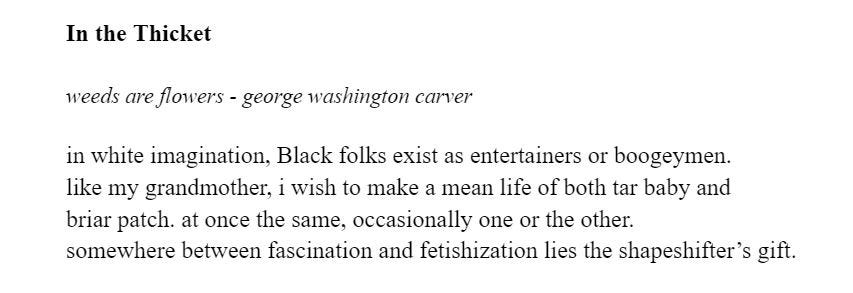

Caught somewhere between the flower and the weed, identifying with both but compelled to choose one or the other. Unwilling to take on the onus of the weed, of the creature that spreads like wildfire, desiring the strength and the sheer beauty of a rose, something that should be treated with care, pruned gently, deserving of softness. One of the poems in my book, Heirloom, begins as such:

I find myself taking up after the plantain that grows in the cracks of the concrete, the amaranthus, meaning “everlasting” bursting through compacted soil, the ragweed, growing below the highway and in the gully. My presence is an indelible marker of what happens when you try to upset the natural ecosystem of an area in pursuit of unearned splendor.

Perhaps a happy medium is found in the teachings of George Washington Carver, an ecologist ahead of his time, who believed so strongly that “weeds are flowers.” In any event, I aim to be as much of a burden to a “monochromatic landscape” as possible.

What am I up to? Well, my Nature Poetry course with Blue Stoop has been finalized and the class begins next Tuesday!

Mark your calendars: a virtual release part for Heirloom is happening 4/20 at 5:30 pm PST/8:30 pm EST! Wear something green, all are welcome ~

Heirloom is going on tour! Do you, your organization or your class need support in climate communications, ecopoetics, culturally informed enviro education and/or Black eco-literature? I am booking guest speaking engagements, gigs and readings for late spring into early fall ~ contact me at my website ashiaajani.com