Free Floating

On giant phantom jellyfish, self-betrayal, and silence that speaks louder than chatter

"Do not leave the arena to the fools." - Toni Cade Bambara, back of a postcard, 1995 Which means, sometimes, you disarm The goon by acting the fool—what they want Is your throat cut, or your heart broken By a dum-dum bullet, or your eyes filling With the void. So they leave with their cartoon Of you in their heads. The instant they turn— the flood waters stopping just before the top step, The hawk grasping feathers instead of flesh— All the small stuff—your sweat beading off Your skin, your breath slowing back from flight To human, you’ve won it. You can pass it on. - Cornelius Eady, "I am here because somebody survived" "Who do I look like, Boo Boo the Fool?" - Black Momma phrase

Exercise – in the next lifetime, if you had to come back as any being, what would you come back as?

Of course, Black.

But also, stygiomedusa gigantea, the giant phantom jellyfish. With only 118 sightings in 110 years, medusa is an expert in avoiding hypervisibility. Medusa, whose gelatinous, velveteen bodies help them survive oceanic high pressures, are considered to be one of the largest invertebrate predators in the deep sea. Considered to be widespread throughout the worlds’ oceans, except for the Arctic Ocean, Medusa has been spotted most frequently on private submersible tourist expeditions. Marine biologist Dr. Daniel M. Moore, whose research theorizes that, given Medusa’s affinity for the ocean’s midnight and twilight zones (depths of ~22,000 feet), one of the only ways humans have encountered Medusa are when they swim higher up to expose themselves to ultraviolet radiation, using these waves to rid themselves of parasites.

Medusa, whose Latin name bears the same as a woman who was raped, transformed into something monstrous as punishment for her own assault, who then uses her tendrils to turn men to stone. Perhaps most of the meaning is in the extremities — unlike stinging jellyfish, who have venomous tentacles, Medusa use their oral arms to engulf their prey. No stone, no revenge, no rewritten narrative to sanitize another’s pain, just hunger and survival pulsing through frigid stillness. We can only hope for that kind of clarity.

Billowing mauve sleeves emerging from a glowing red bell, Medusa’s arms remind me of Mami Wata’s translucent flesh, a soft yet menacing invitation to be consumed, and perhaps rewarded for your devotion. And yet, sheltered by Medusa’s voluminous folds, Thalassobathia pelagica, pelagic brotula, finds nourishment and protection in a deep sea predator. In fact, their relationship is one of the first documented symbiotic relationships of ophidiiformes (cusk-eels, brotulas, pearlfishes, etc.): in exchange for food and shelter, pelagic brotula removes parasites from Medusa. Even when separated, the two species find their way back to each other, due to the low frequency vibrations Medusa emits. Seafloor, as much a graveyard as it is a womb.

A kid raised on Animal Planet and National Geographic, I never liked when nature documentaries put music over their footage. I think it distorts representation, fools us into imposing a very human meaning onto nonhuman subjects. Instead of crashing cymbals and plucked strings, I’d rather hear the sound of paws on prairie, claws stripping wood, long stretches of silence pockmarked with bubbles and waves, whale song retrieved from before they went silent in a nutrient-deficient hell. A few years ago, I read Tao Leigh Goffe’s article “Unmapping the Caribbean: Toward a Digital Praxis of Archipelagic Sounding,” about sonic traditions intermingling with (un)mapping the Caribbean. Goffe describes how sonic impositions are another layer of colonization, specifically referencing the chatter of gentrifying hipsters in predominantly Caribbean New York Neighborhoods. Sound shapes the landscape. Silence punctuates aural topography. Learning about the necessity of silence (a monumental feat for a Gemini), is a lesson in appreciating its opacity. And then again, in her audioessay “Listening Underwater: Silence as Fermentation,” Goffe writes, “Silence forces a confrontation with the self and origins. Collective loss often across oceans defines diaspora.”

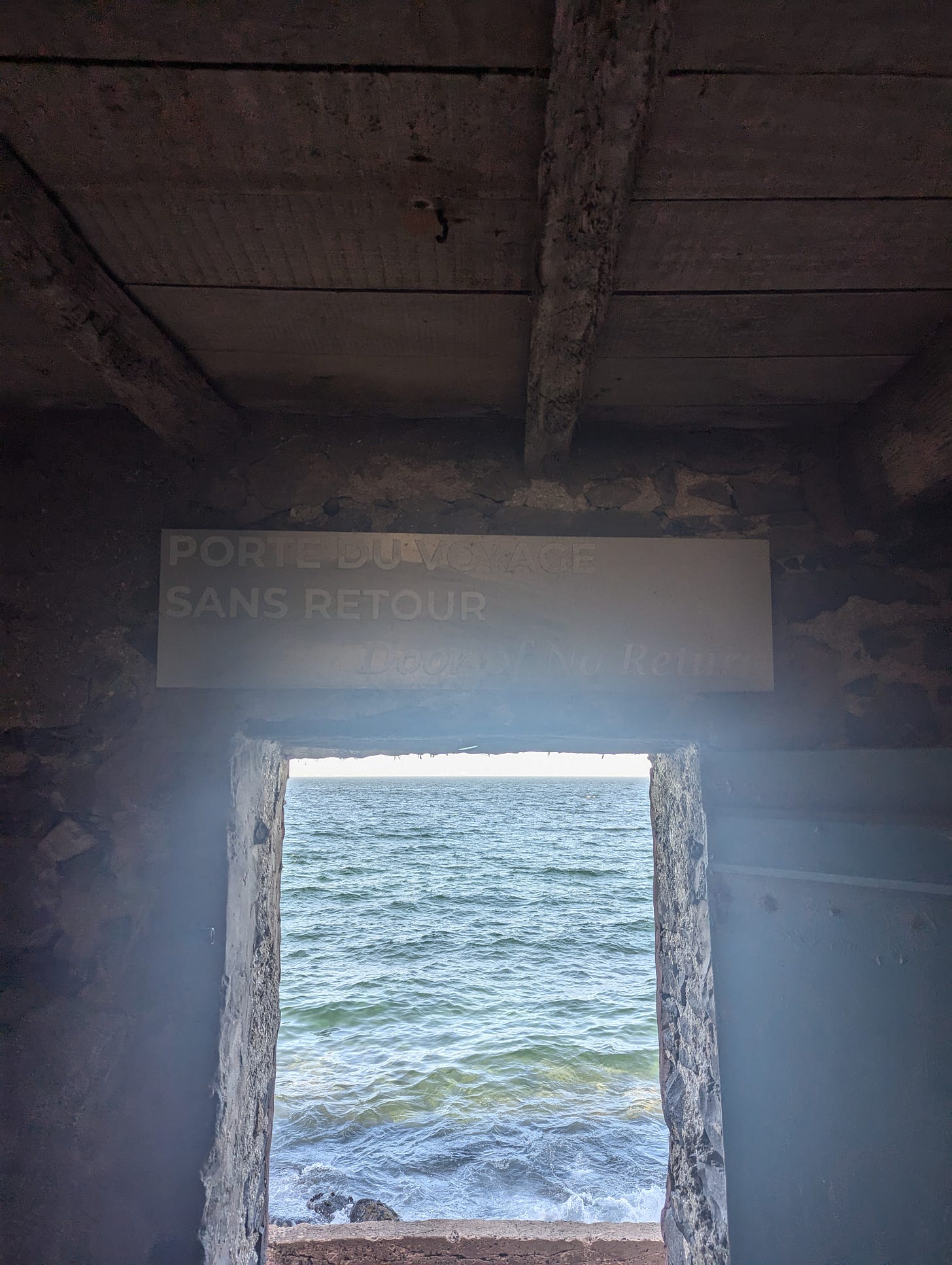

I could watch jellyfish swim for hours — their silent motion steadies me. Despite a healthy fear of the ocean, I often wonder what technology would allow it so I could swim with Medusa, without my lungs being pulverized in the ocean’s obsidian depths. This year, filled with record (and deadly) flash flooding across the globe, ocean acidification planetary boundary being crossed, hurricanes hammering the Caribbean, I spent more time than I ever have in the past sitting at Yemaya’s shore. Whether in Cuba, the Bay Area, Massachusetts or Gorée, I found myself staring out into her ethereal blue expanse, crying, praying for a flood that changes everything, or as Franny Choi writes,

“Lord, I confess I want the clarity of catastrophe but not the catastrophe.

Like everyone else, I want a storm I can dance in.

I want an excuse to change my life.”

I think more than anything, I want to be fully consumed by something bigger than me. I suppose this desire is foolish.

Question: was Milkman’s desire to fly foolish?

Lately, I’ve been thinking of my own foolish longings. What remains of a disappearing planet, staving off 2 degrees Celsius of planetary warming, retrieving all the deceased who died too early from the banality of evil outside their control. With each passing year, I am more aware of my own shortcomings, and how they are amplified by our collective neglect. Lord, I have been a fool. When the party ends and the lights come on and you’re left alone to clean up another’s mess, you wonder what is the point of all this laughter. At some point, we are all the butt of the joke.

Yes, we left the arena to the fools – because we are extensions of those fools. And this compliance is a discursive practice. Everyone has an inner fool (and of course, some have more pronounced fools than others). Our apathy feeds that inner fool, and it also buttresses fools who wield power indiscriminately, chipping away at anything living in defiance — a slow violence. Fatigue is the point, so we lean into the absurdity because (if we are lucky) we will not bear the brunt of the terror. To live in the imperial core is inherently a foolish existence, because your entire life is made possible by exploitation and extraction, suffering outsourced elsewhere…sometimes internally. Our foolishness is not stagnant, not without repercussion.

Depending on one’s perspective, a fool is someone easily manipulated, or someone capable of great manipulation. Because they appear to be unsuspecting or dense, no one takes the fool seriously until it is too late. By then, the catastrophe has made its way to your doorstep, and/or the fool has run off with all your gold.

We as a collective have a deep issue with acquiescing to fools. The meme-ification of our governing class is one glaring example of this — another, staving off difficult conversations at the site of crocodile tears. In doing this, we grant grace and levity to folks who would rather see us incarcerated or dead. 2025 has felt like a large cauldron, and we are all the frogs waiting at the bottom of it, as evil hands turn up the stove’s heat, waiting to see how much temperature we are willing to withstand. It’s a terrible experiment, and it’s happening at times, with our foolish consent. How do we disentangle ourselves from the circus?

But there is another reading. Come, take a cold plunge.

When I was a kid, I used to watch Martin (1992-1997) with my dad after school. Hustler Man was a minor recurring character on the show, selling everything from tires to barbecued pigeons on a skewer. Played expertly by Tracy Morgan, Hustler Man is meant to be a silly representation of neighborhood boosters, conmen and resellers, never without a hustle or a way to make a quick buck. He is written as someone to ridicule or not take seriously, but at the end of the series, Hustler Man gets the last laugh. And the question remains, is Hustle Man the fool for his charlatan antics, or are we the fools for ever doubting the Cat with nine lives?

In late November, Adi Magazine published my essay “Islands in the Sky,” a meditation on endangered spider species, trickster narratives and marronage. Sometimes used interchangeably, the fool and the trickster are two distinct archetypes, even if they play similar roles in folklore. The fool often faces his own consequences, whereas the trickster tries to exterminate theirs (sometimes successfully, sometimes not, the distinction is in the effort). The fool can get away with saying things others can’t. The fool should know when the fun is over. At the end of the party, who remains laughing? Who returns back to themselves?

To be known is contextual. Fools of great notoriety, fools who learn by doing, who dare to try, sometimes blinded by their own hubris, sometimes buoyed by courage, always shaped by luck. Any fool worth the salt in greens, is above all else, an observer, while only letting a piece of their true self be observed. A good fool wears a mask. A good fool does not succumb to the power of being unknown, so much so that they abandon themselves. A good fool does not forget the mask is there.

Because the fool meets an absurd existence with absurdity, he achieves an ephemeral freedom. Less a person, more a costume. Can the fool still be a fool without an audience? Is a fool still a fool without the protection of a king? Do the fools and kings grow alongside each other — is one dependent on the existence of the other?

It is predicted that, if we continue fossil fuel consumption at our current rate, places like Miami, New York City, Panama City, Vanuatu, Shanghai, the Everglades, New Orleans, and parts of San Francisco, Fremont and Foster City, may be underwater by 2050, if not sooner. Being submerged is a terrifying concept because on dry land, we at least have some form of control. We feel grounded; we can at least breathe. In a society that often builds against the landscape rather than with it, we have much to learn. Underwater, we cannot fool ourselves. Underwater, we are desperate. Jellyfish are indicator species, which means changes in their population can reflect general changes in their ecosystems. They move carbon through marine trophic levels, and they serve as a food source for a number of aquatic creatures such as sea turtles and large crustaceans. Even in death, jellyfish carcasses serve as necessary nutrients for bottom feeders. Jellyfish population numbers are increasing — which is not a good thing. Jellyfish blooms are occurring around the world due to overfishing of their predators and ocean acidification. In the case of Medusa, who is considered a predator species, who we still know very little about, a more recent sighting was only made possible after an iceberg the size of Chicago split from the George VI Ice Shelf and Medusa was spotted swimming under it.

Our planet does not speak to us in metaphor or comic rebellion. Sometimes the silences say more than the cacophonies. While we have only scratched the surface of Earth’s terrestrial landscapes, we know even less about the aquatic ones. On land, we can fool ourselves. In the water, we are stripped of pretense, beholden to a vestige more ancient than our foolish enclosures. Our quietude, our liberation defined by our willingness to go deep. To submerge. To pull courage from waters that challenge the rigidity of our separation.

Medusa stretch out their arms and take what they need, steadily moving with the oceans’ currents. Perhaps that’s all there is to it — using our opposing skills to support a collective survival.

Personal announcements:

Tending the Vines (Timber Press, 2026) has a pub month! September, here we come; Virgo or Libra…that is the question.

I have a very beautiful new website designed by Willie Lee Kinard III (iykyk), an incredible poet, designer, and author of Orders of Service (Alice James Books, 2023).

But before that, so, so, so much rest.

Currently Reading:

Blood in My Eye by George Jackson